SEARCY ’46-’56 – Part 13

Chapter Eight

Tom Pry

Wheels – Trains

For a town that was never located on the main line of a major railroad, Searcy has quite a history with trains.

So do our neighbors, of course. Bald Knob was reportedly named by a railroad crew after a small, treeless hill near town. The popular story in Kensett is that, when the MoPac surveyors came through in advance of the tracklayers, and asked where would be a good place to put the rails, locals told them, “Well, you kin set ‘em here, or you kin set ‘em there.”

The only one of which there is still a presence is, of course, the DK&S, the Doniphan, Kensett and Searcy. This actually started out as the Kensett and Searcy, and then the Missouri-born company for which my grandfather worked moved their hardwood mill down from Doniphan, MO, and opened up outside Kensett.

(Sidenote: that mill’s primary product was turning out hardwood spokes for automobiles, and had already cleaned out most of the hardwoods within a 50 mile radius of Joplin, MO, and Blytheville, AR, before it got here – to ultimately leave here and move to Glenwood, AR, near Hot Springs).

****************

The Railway Express office had a plaque on the wall proclaiming it was run by the Rock Island Line. If a very shaky memory still functions to some degree, that means it was served by a spur from Hazen at one time, probably over that same DK&S stretch of track.

In fact, let’s deal with good old REA Express (the final name for Railway Express) right now.

Railway Express was started by a consortium of railroads – most of them, in fact – to deal with the problem of LTL (Less Than car Load) shipments: a box of this, a package of that, etc. These offices were much better equipped to deal with that sort of thing than the individual railroads, and also eliminated the potential problems caused by shipping a package starting on one railroad, and finishing its journey on another: who got the package from the first rail line to the second?

Enter what finally came to be called REA Express, a company that, like that buses the railroads had spawned, ended up becoming a separate entity, for all practical purposes. The rates were reasonable, the offices were all over the place, and the service was fast, since the REA cars traveled with the passenger trains.

It was the demise of the passenger trains that gave UPS its opening to eventually expand nationwide. (United Parcel Service, for what it’s worth, started out as a package delivery service for the Chicago area. It was begun by a group of department stores, lead by Marshall Field & Co., that decided it was foolish for each downtown store to maintain its own fleet of delivery vehicles).

Coming down Spring Street towards City Park, did you ever wonder why the Northeast corner of Spring and Pleasure, across from the Library, is elevated so high above the level of the park? It’s because that parking lot was the Rock Island terminus, and the REA office sat where McKinney Supply, Dr. Nevins et al are now located. Eastbound, if you stay on Pleasure and cross Main, you can see some remnants of rails in several patches between Main and the apartments near the Harding campus, on the north side of the road.

The DK&S also terminated at Main Street, on the east side. The old terminal still stands there, not quite abandoned by its present owner, the Union Pacific. Within the last couple of years, the DK&S line was terminated at Benton Street, so rolling stock no longer comes to downtown Searcy but, growing up, I can still remember working boxcars parked on the WEST side of Main Street, alongside what is now Beebe-Capps, right behind the feed store.

That stretch of track along Market Street was very busy, once upon a time. It had started out as a WOODEN rails track, with cars pulled by mules. Later, it was changed to iron rails and trains actually started running on it, especially when Galloway College was starting and ending a school year. That stretch of track started as an attempt to connect both with the Missouri Pacific and the Fulton and Cairo, which refused to come to Searcy because Searcy wouldn’t cough up some inordinate amount of money. (Searcy got the last laugh: Searcy’s still here, but where is the Fulton & Cairo? In fact, where IS Fulton and which Cairo?).

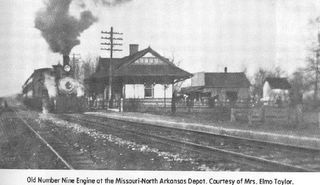

Old #9 at the M&NA Terminal

The star of the rail show in Searcy has to have been the Missouri & North Arkansas.

Envisioned originally as running from Joplin, MO, to Helena, AR, it ended up running from Springfield, MO, to Helena. Along the way, it seemed to hit every wide spot in a very bumpy road: Pangburn, Crosby, Eureka Springs .. all told, about 40 towns and settlements. The first run in this area came about in 1907, out of Heber Springs to Searcy.

I say “.. a very bumpy road ..” because it cost a fortune to build that road; that being the case, it had been built on the cheap, with only light ballast (the gravel between the ties) and even lighter rail. Rumor has it that some passengers took the precaution of ingesting seasick pills before taking a trip on the line, since the trains had a tendency to swing and sway.

(The always-interesting Bob Sallee, in the Dem-Gaz of 12/8/98, quotes the late “Bub” Harrison as saying that trains were such a rarity that about 100 people turned out in Letona in 1907, waiting to see their first train, the one coming down from Heber Springs. Harrison said that many of the women were carrying parasols – “the best thing on earth to scare a horse.” As the train neared the station, “.. some crackpot hollered, ‘You women better close them parasols. You’ll scare that engine!’” It is reported that, at that warning, about half the parasols closed).

The M&NA quickly acquired a canard claiming the letters actually stood for the “May Not Arrive,” because that was the case all too often. One major bridge was shoddily built, and a bad storm dumped it in the drink. A number of bridges were burned, especially in a very vicious strike that took place in the early 20s, that took the railroad out of service for almost a year, before hungry strike breakers got the wheels turning again. They didn’t turn at all for eight months.

(My partner in cockeyed history, Ernie, faintly remembers taking excursion rides out to Crosby, on something he remembers as “the Moose,” a self-powered single unit. Turns out, it was the “Blue Goose,” a blue locomotive and two cars, one for passengers, one for freight).

But, as Searcy’s only through railroad, the M&NA acquired a certain amount of fame. Probably the high point of its history was in early 1937, when the very first automatic railroad safety gate in the entire southwestern United States was given its sendoff right at the corner of Beebe-Capps and Elm Street. Even the governor came up to give a speech for the occasion, no small thing, considering the condition of the roads between Little Rock and here.

In 1943, right in the middle of the war, the railroaders went on strike again. Despite a change of name to “The Missouri and Arkansas,” and a new owner acquiring it in 1945, that railroad never ran again.

In the spring of 1946, I saw one of the last vehicles to come down the line. It was what is called a “hi-railer,” a pickup/utility truck that can swing down steel wheels to ride on the rails, leaving the rear tires to just supply motive power. I’d guess that it was surveying the route to see if it could still handle rail cars, so that rail could be picked up and placed on flat cars as the Last Train came through, a work train.

There are few people around who remember the M&NA and where it ran, even though a lot of people here duplicate a big chunk of the local route every day.

??

Judging from its location, it seems a fair assumption that most of Beebe-Capps, from Healthcorps to East Line Road, is built on the abandoned M&NA right-of-way. At the western edge of town, just past the Conoco gas station, Highway 36 takes a sharp dogleg to the left before turning west again. That dogleg is where the M&NA diagonally crossed state highway 36, going down about a mile, straight as a rail, to cross what is now North Valley Road, on its way to Crosby; this was where, in 1946 and 1947, I saw the last of the M&NA as a workable railroad.

The name is still around, of course, worn by a “short line” that carries freight from a point about 50 miles north of Springfield down to Ft. Smith .. but it's just not the same as it once was.

Then again, it never is, is it?

(Series originally published late 2003/early 2004 on the old site).